Last week, I heard back from the VA. Yet again, they don’t consider my chest pains to be service-connected. This reality kind of floored me. I actually opened up to them in my December 2016 claim and while it might sound silly to say such a thing, in 2007, I kept things simple.

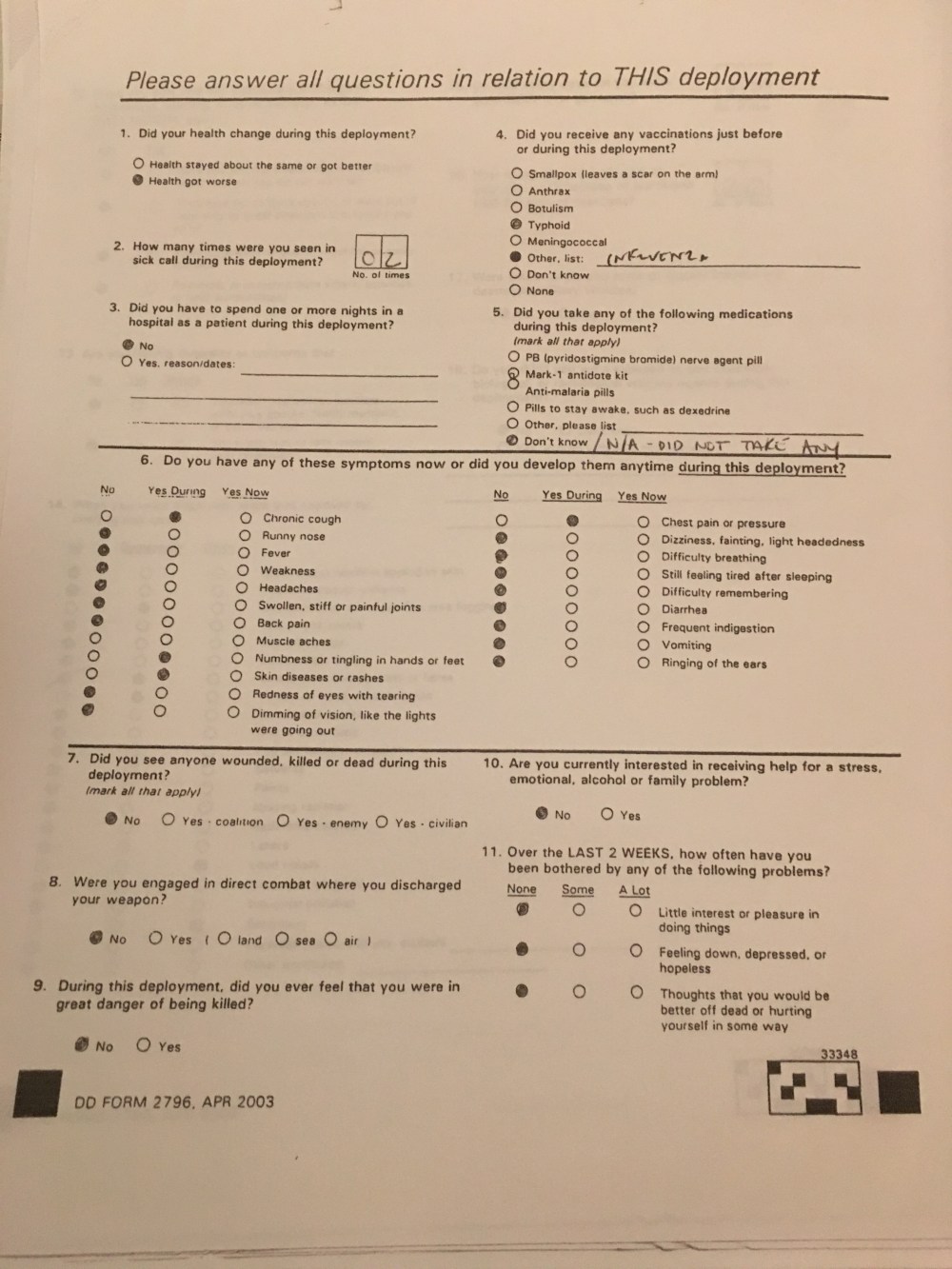

I didn’t tell them about Captain Brock dying. I didn’t tell them about my kind of work. I didn’t emphasize my exposure to mortars, although that information was part of what I listed in my records about different types of exposures while in the Marine Corps. Back then, I was dealing with chest pains and I knew I didn’t have them before I served. They started at the tail end of my first deployment, continued after I returned, and remained a part of my life through separation. I just needed the VA to understand at my point of separation the chest pains were still ongoing and I felt they were related to my service in Iraq in OIF 2-2.

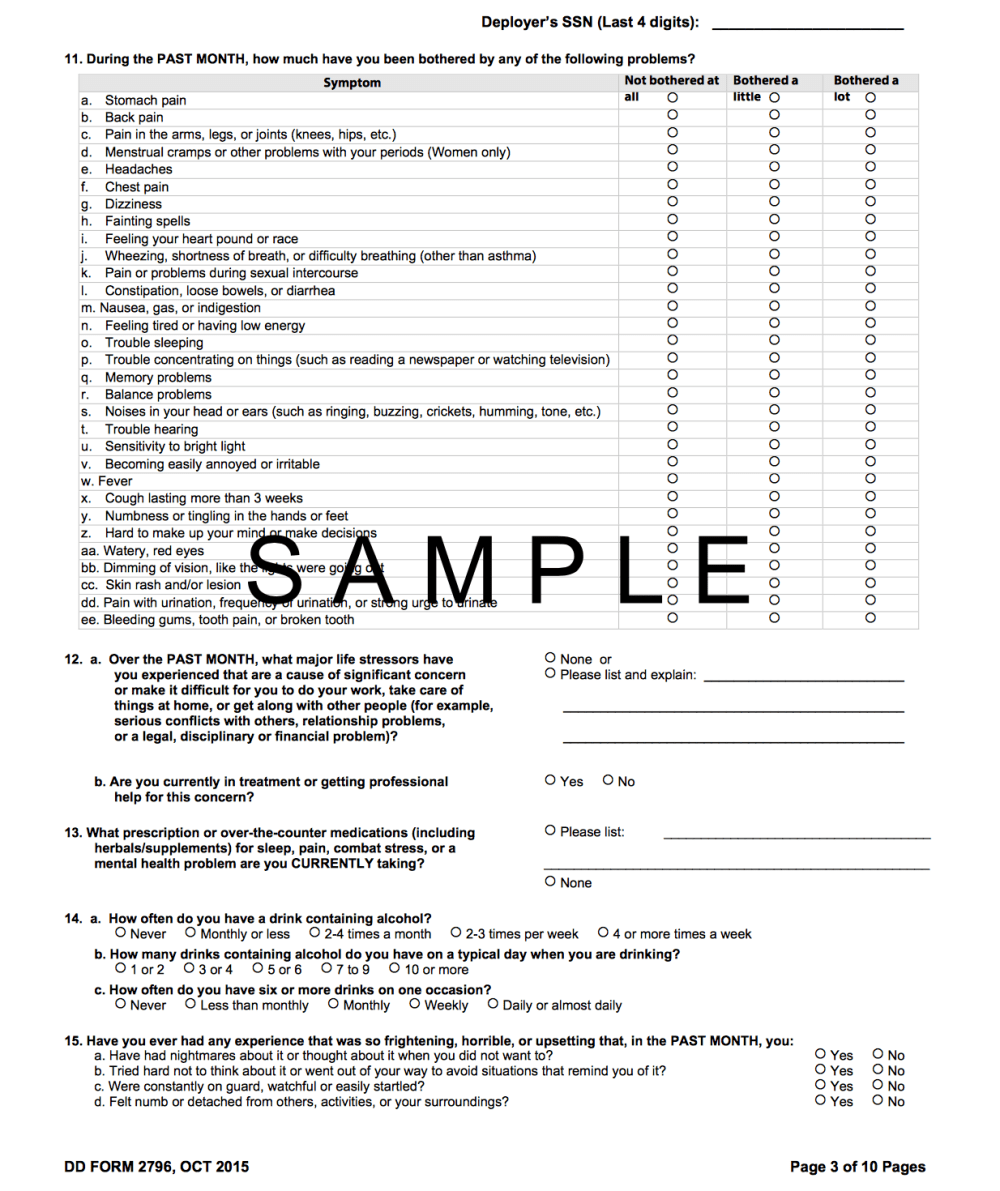

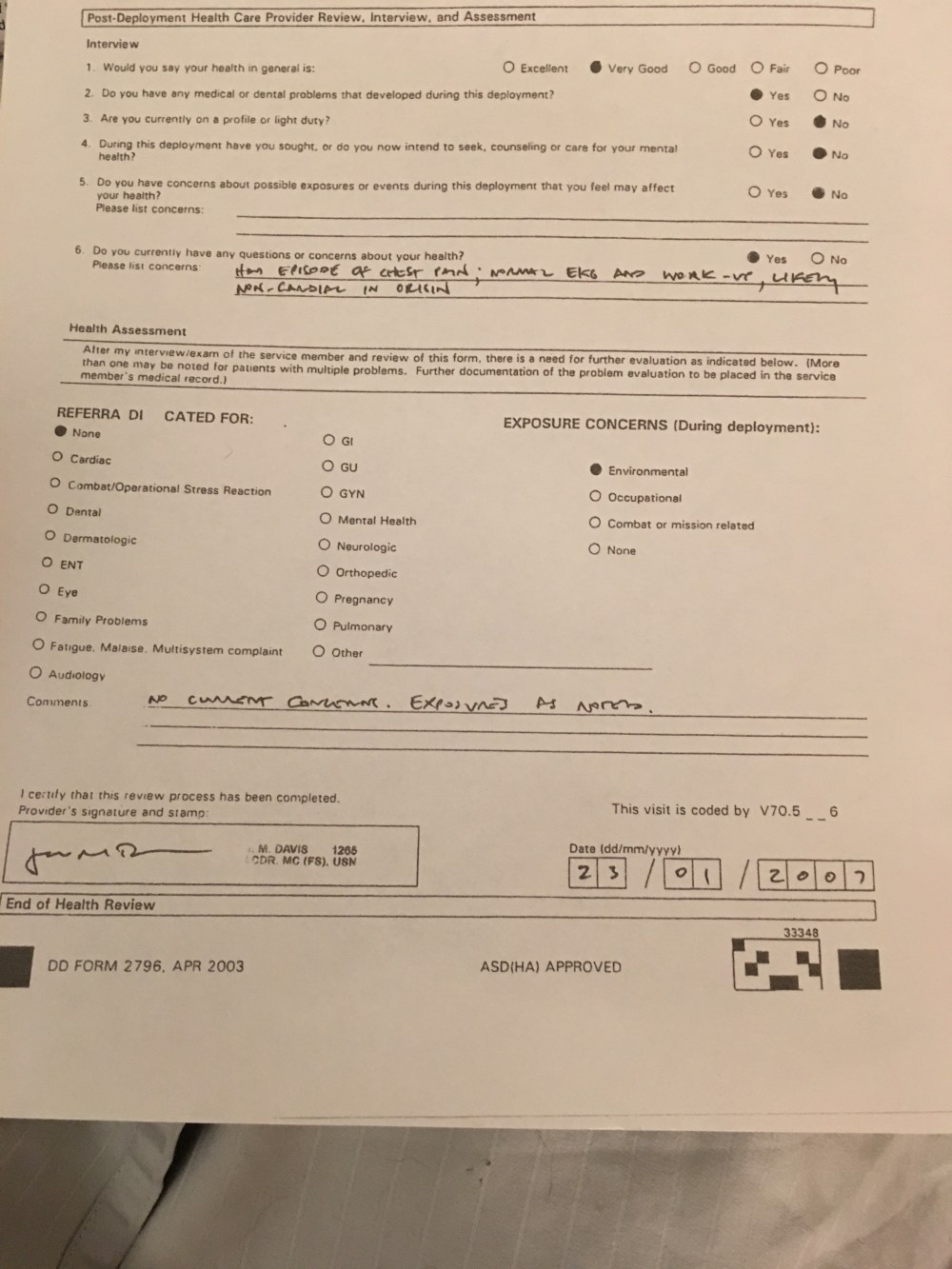

If I had realized what a miserable experience it is dealing with the VA on the disability compensation side of the house, I think I would have pushed harder to find the right medical support while I was in. For the few times I was willing to subject myself to medical about this condition, every person wrote ‘non cardiac origin’ for the pains but no one wrote in a diagnosis or suggested getting additional feedback on my situation. What’s more infuriating is the parts where it reads ‘exercise induced stitch.’ Seriously, in the twelve years I’ve dealt with these pains only the primary care provider I’ve dealt with most recently has delved further into this issue and offered different suggestions because the pains were getting to the point they were destroying my quality of life during waking hours and would interrupt my sleep.

For over a year now I’ve wanted to have a conversation with you all about the Pre-and Post-Deployment Health Assessments and I think with this other VA encounter, I have the right foundation for this discussion.

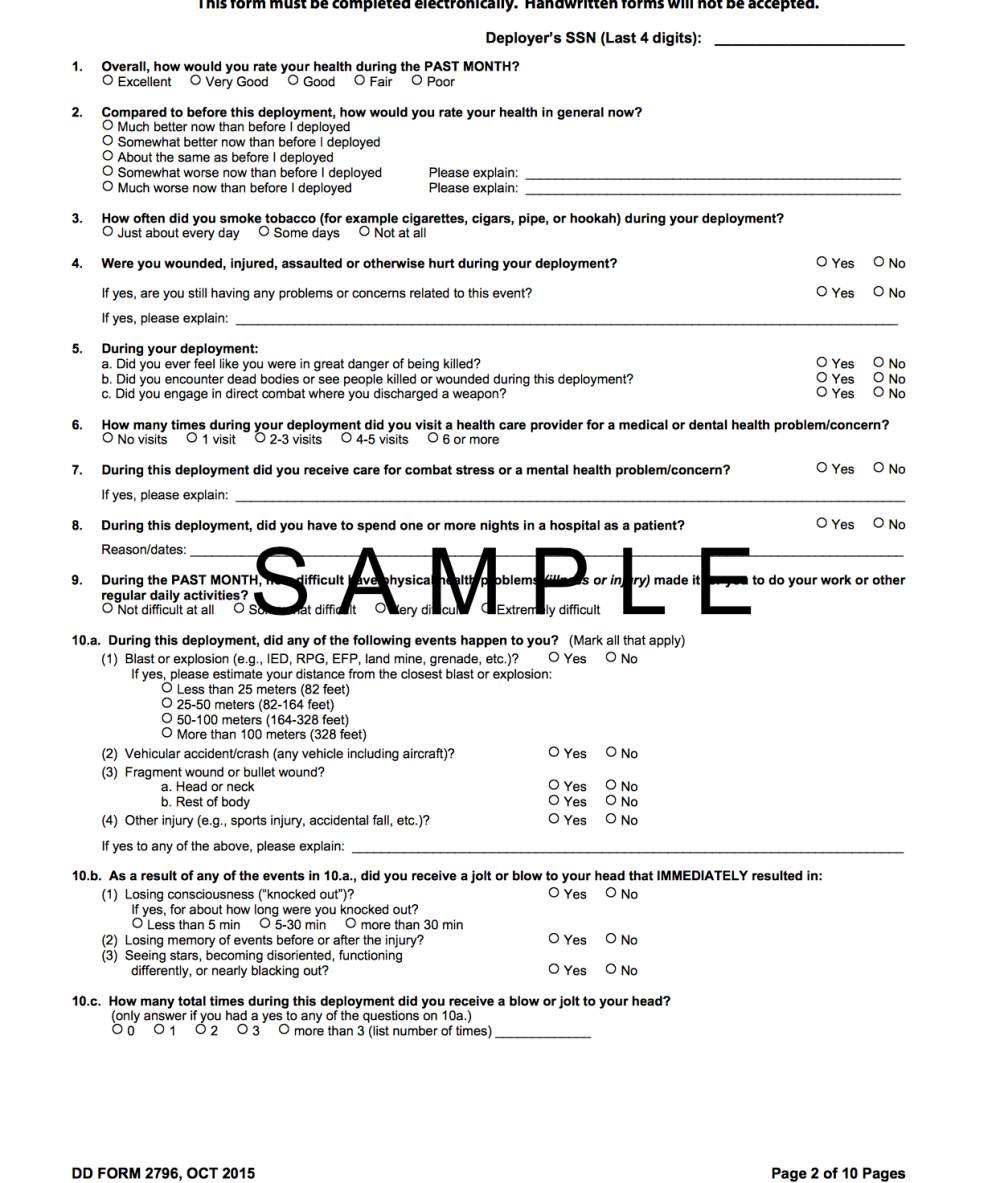

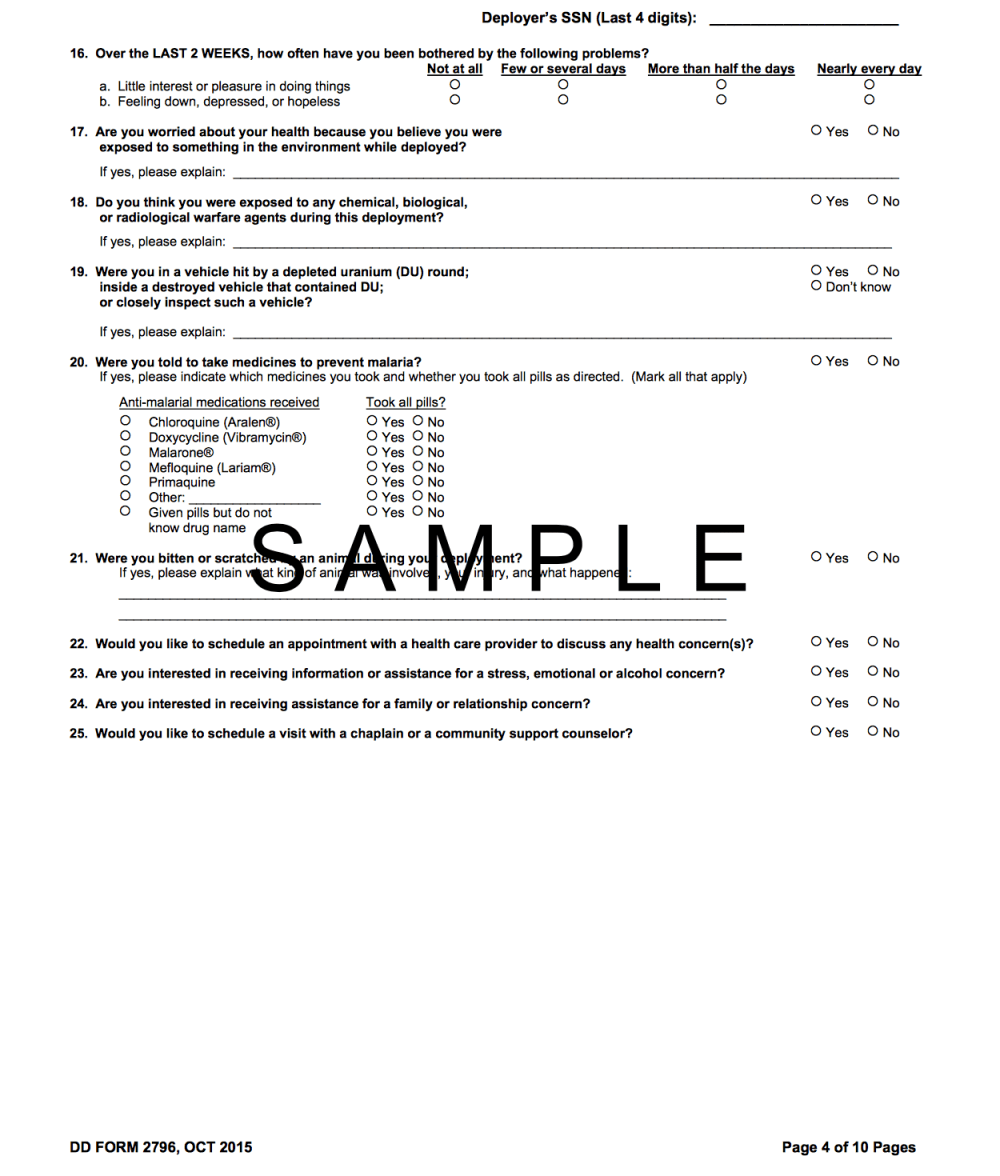

The VA does not know our deployments the way we do and part of the problem is also the way the system requires ticking off boxes, ineffectually asking and not asking the right questions. The forms we complete do not necessarily represent the types of situations we may encounter; let’s be honest here, the VA will never have records from the Marine Corps and/or the US government that 175 United States service members died during my deployment and these numbers best represent the information I was feed every day as part of my work in our operations center. I only know this information because I was determined to find a way to discuss my deployment, to shed light on other aspects of war no one seems to look closely at but is an important job all the same. I am only privileged to know this much of the extent of my deployment thanks to Military Times data.

In cases like mine my work was classified secret so how was I suppose to honestly fill out the forms? As well, even if I could be honest, there also is not a sense of privacy to complete the forms properly not that I would have trusted completely it in full disclosure. On my first deployment, I was the only woman on my team so I felt implied pressure to not be the “weak link” and during the second deployment a lot of stress from the first deployment crept up that I was not willing to discuss with my command. Nor was my situation helped by the fact my chest pains occurred on deployment and yet again, no real resolution came out of getting them checked out.

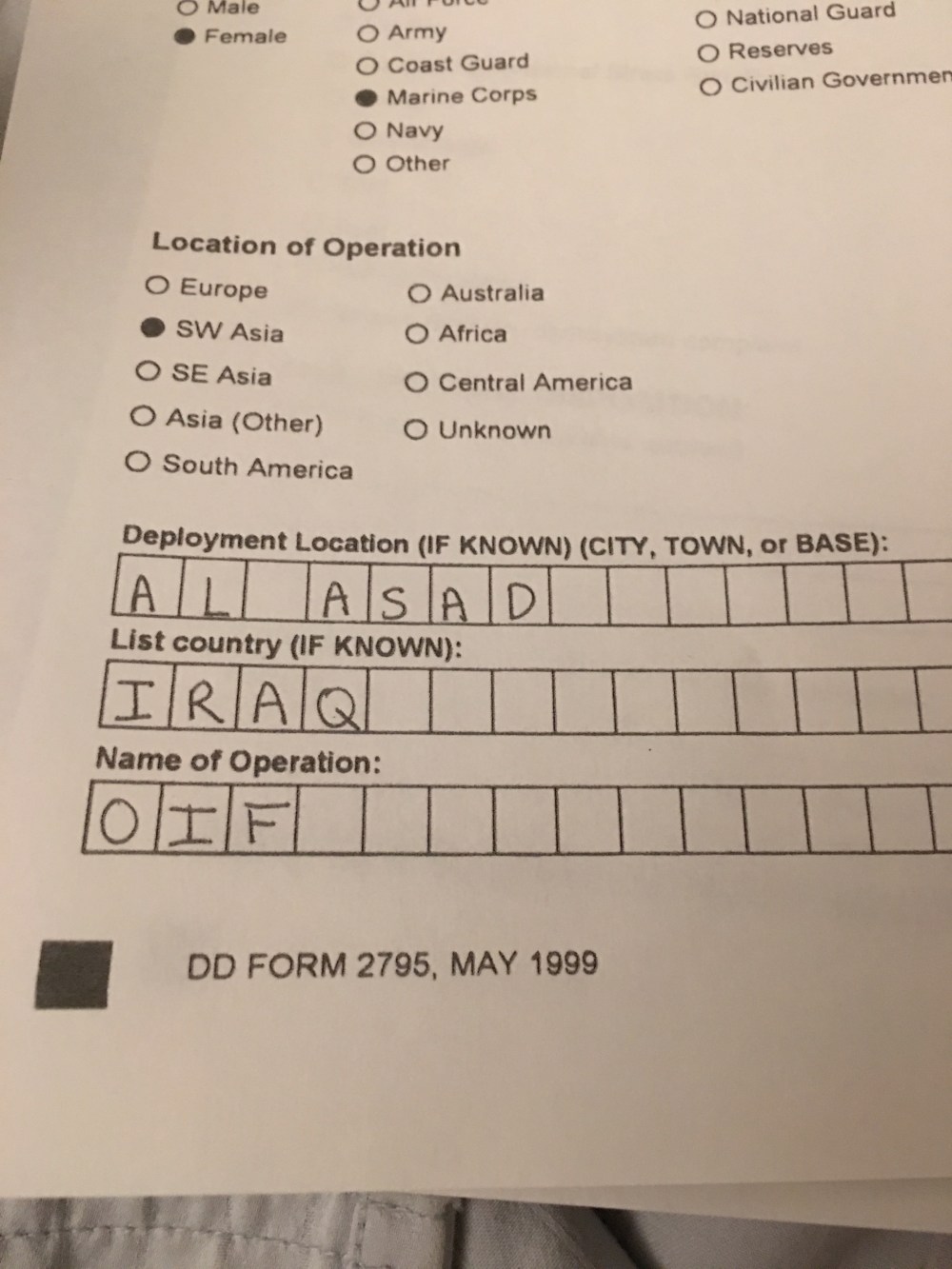

My apologies I currently do not have snapshots of my first deployment paperwork. eBenefits is being quite a disappointment and again not allowing me access to my military records. The next time it’s available, I’ll try to download all my copies so I can share those details with you. For now though, we can press forward using information from my second deployment documentation, the pre-and post-deployment health assessments.

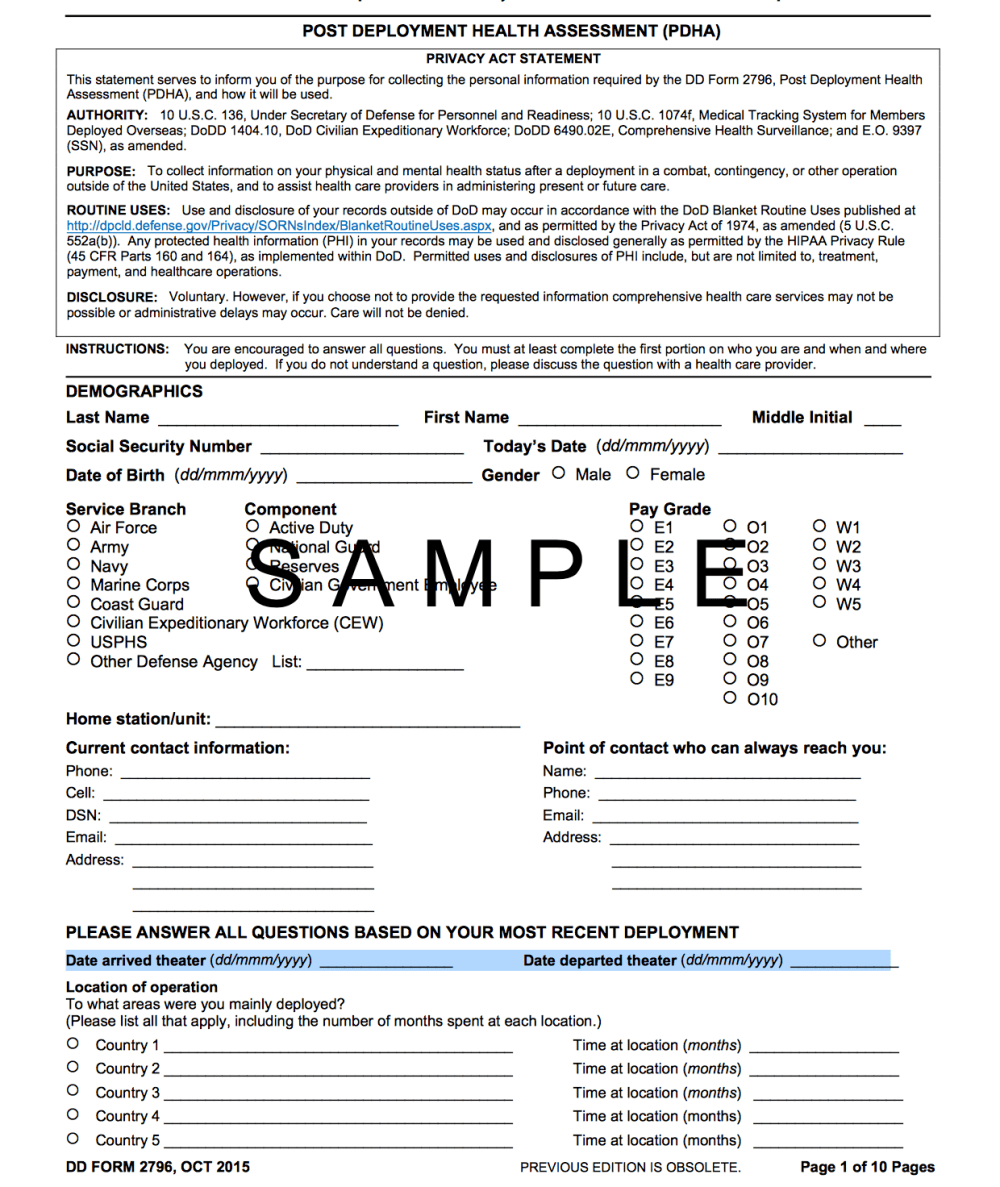

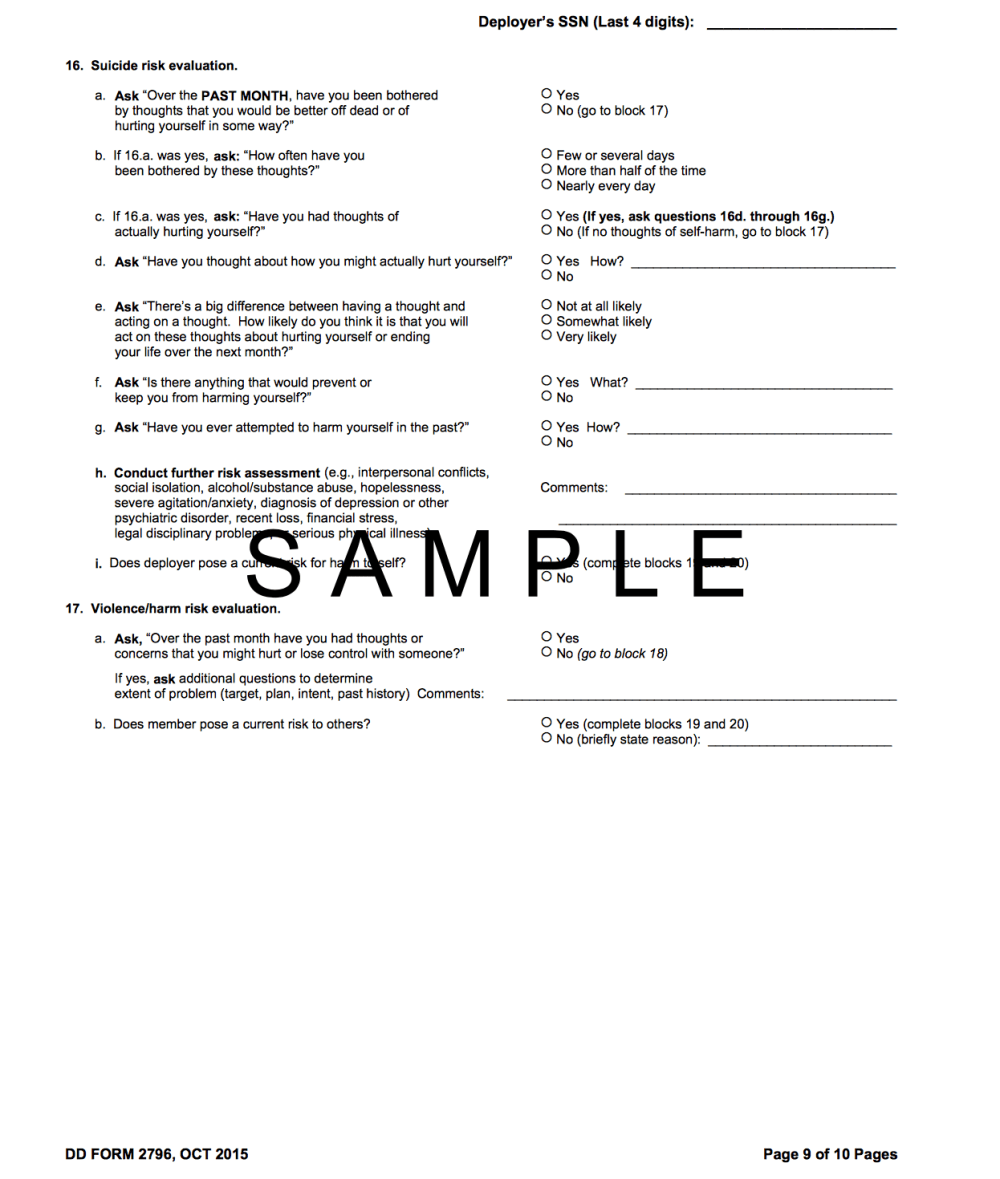

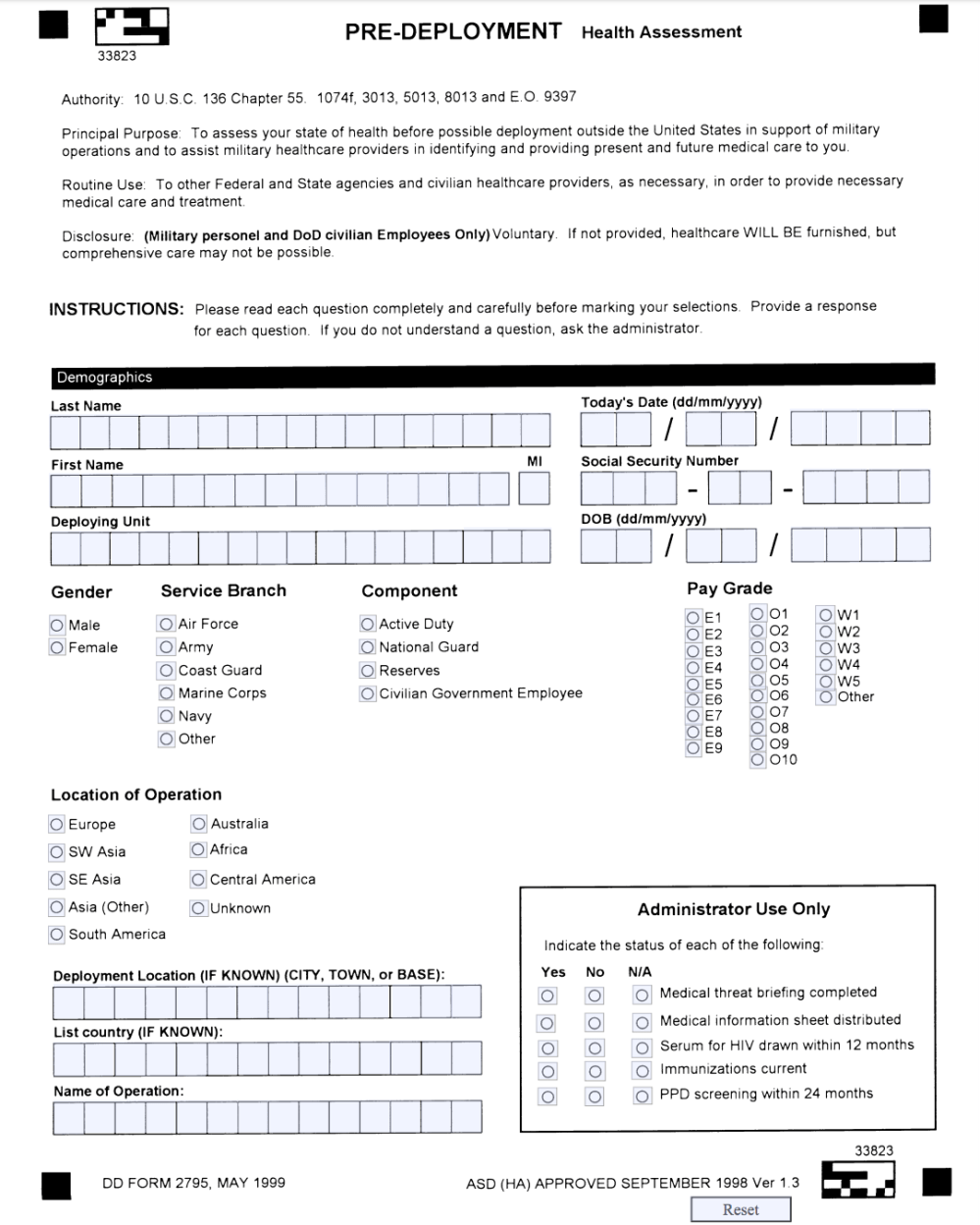

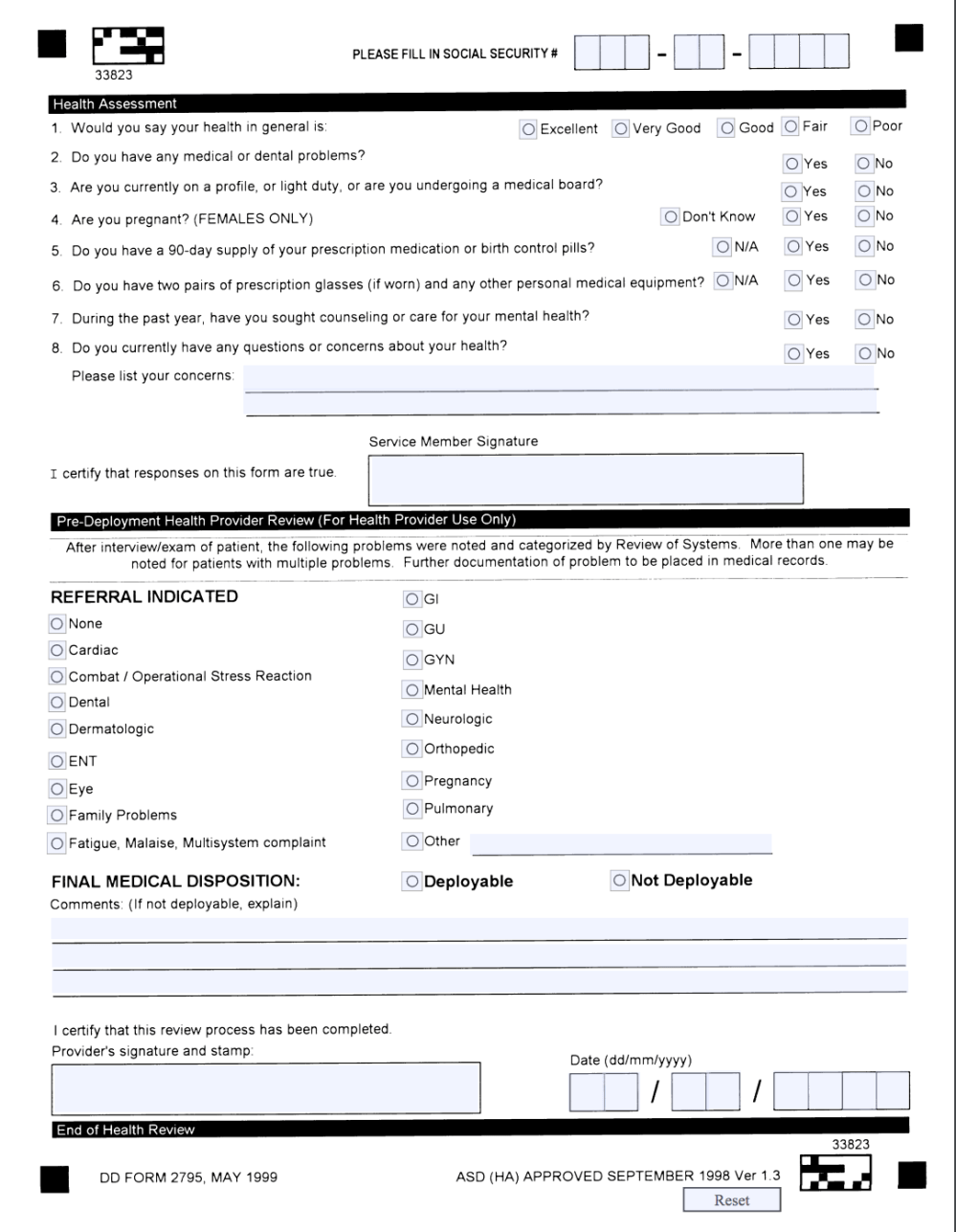

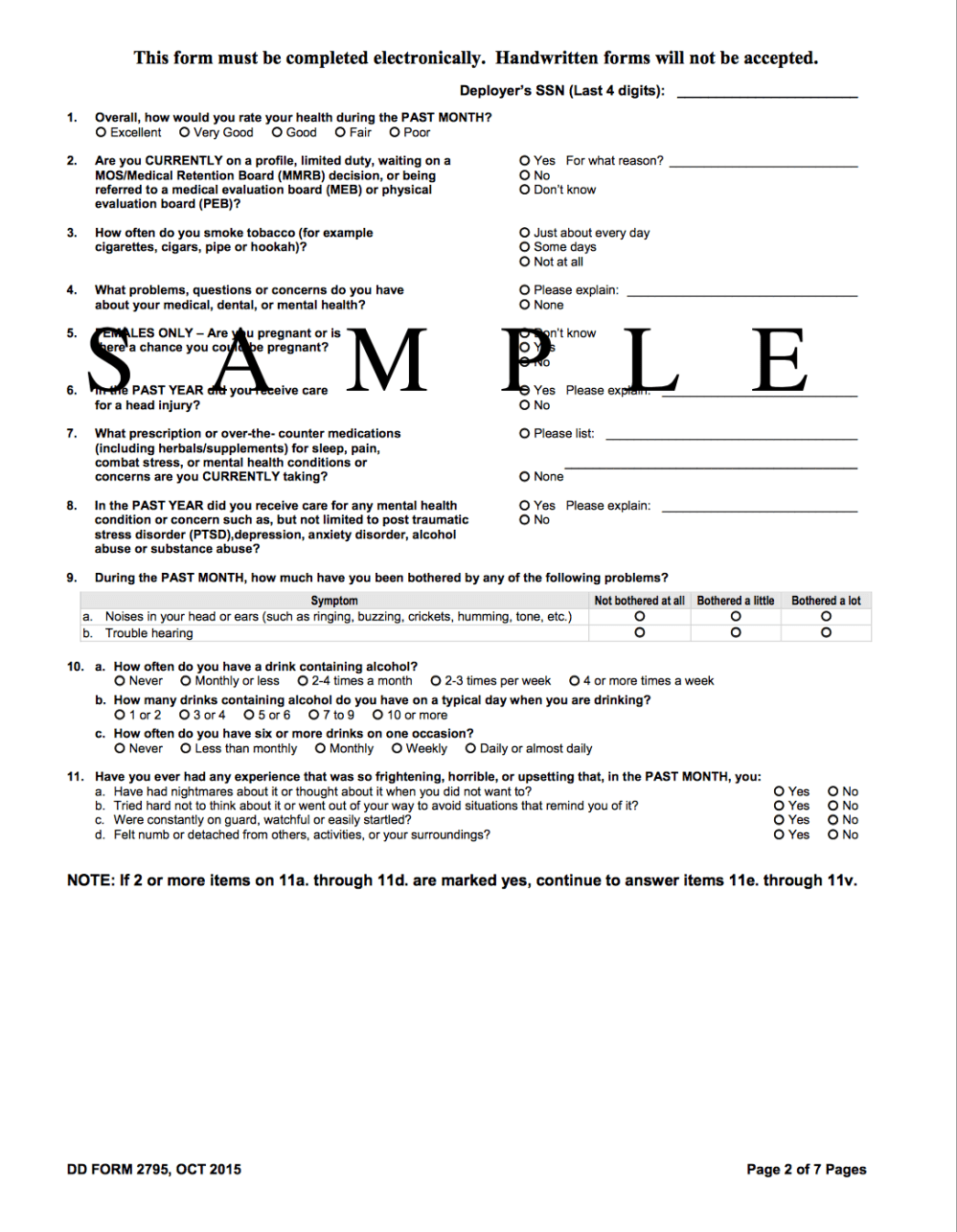

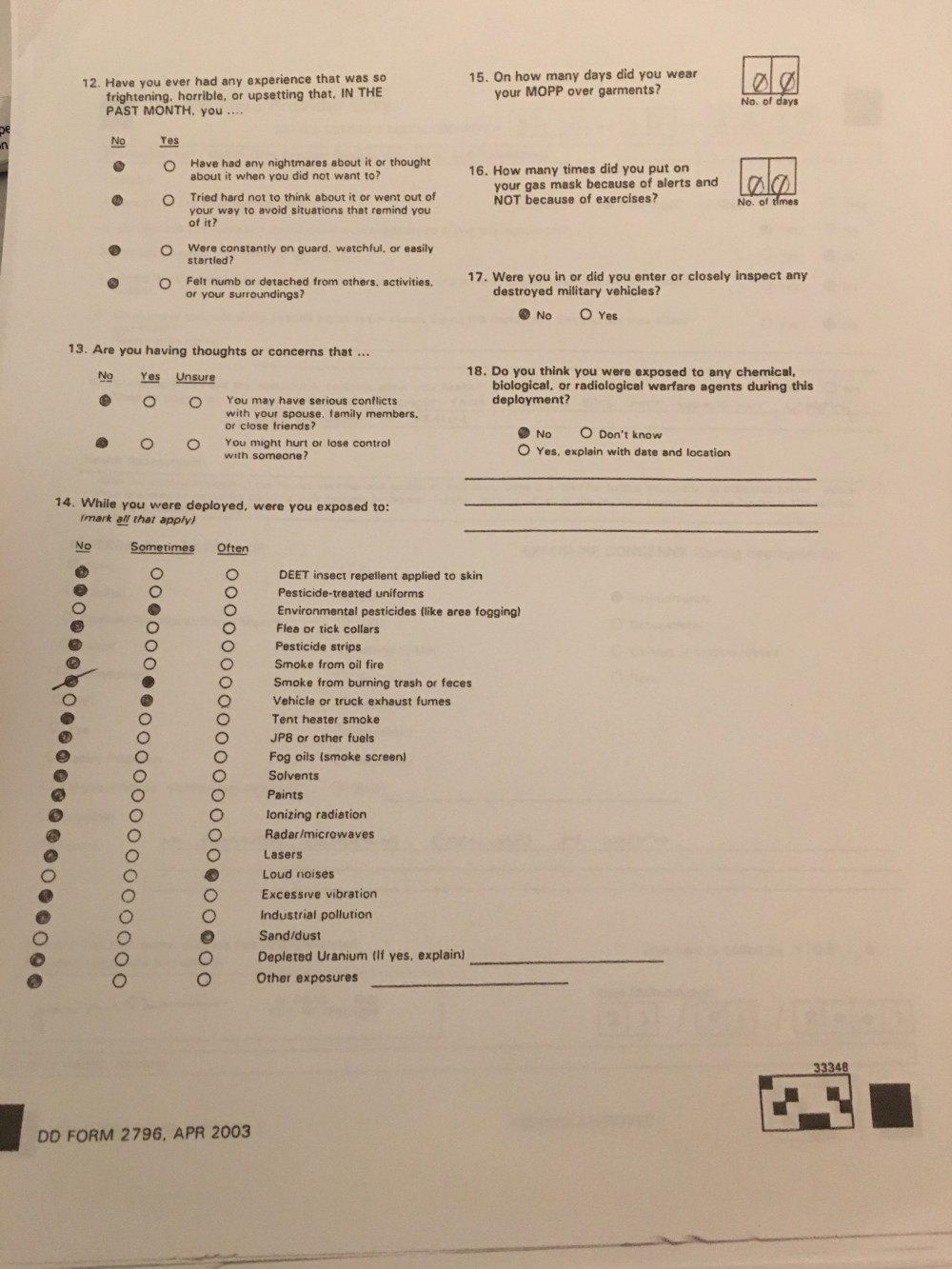

I’ve cut off segments of the documentation as my copies contain my Social Security Number but for greater clarity on this issue, below are fuller snapshots of the pre-deployment health assessment form that existed during my period of service.

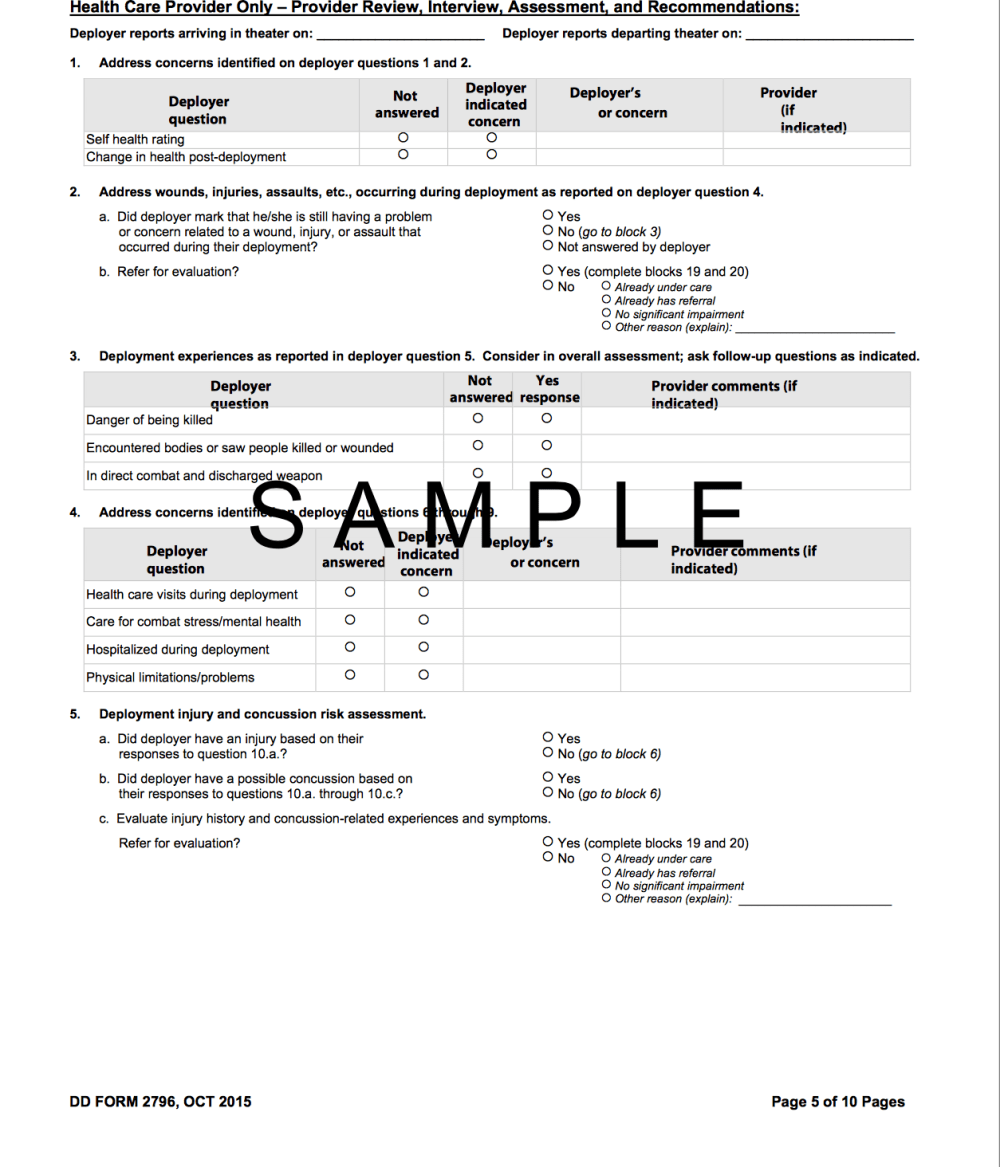

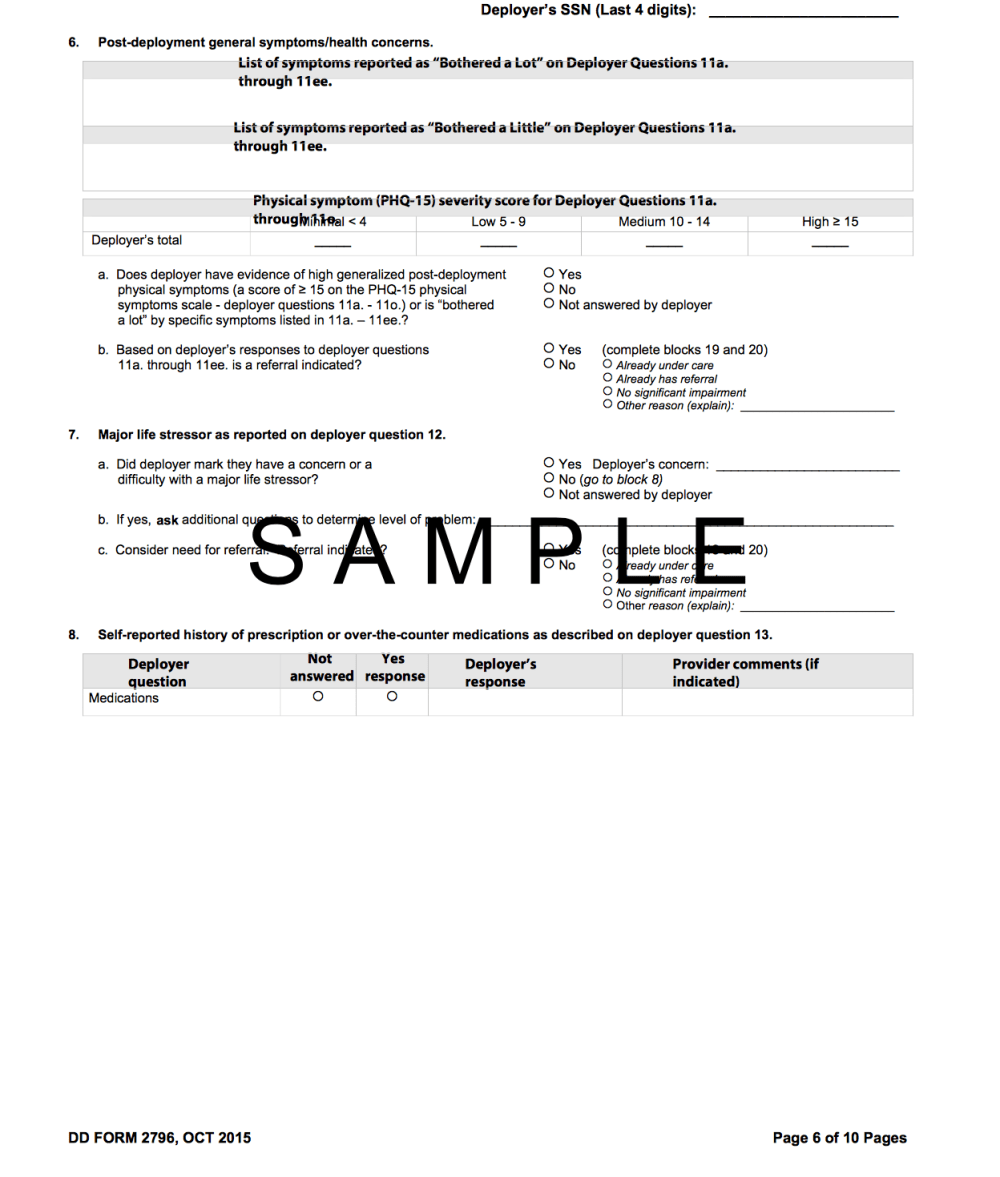

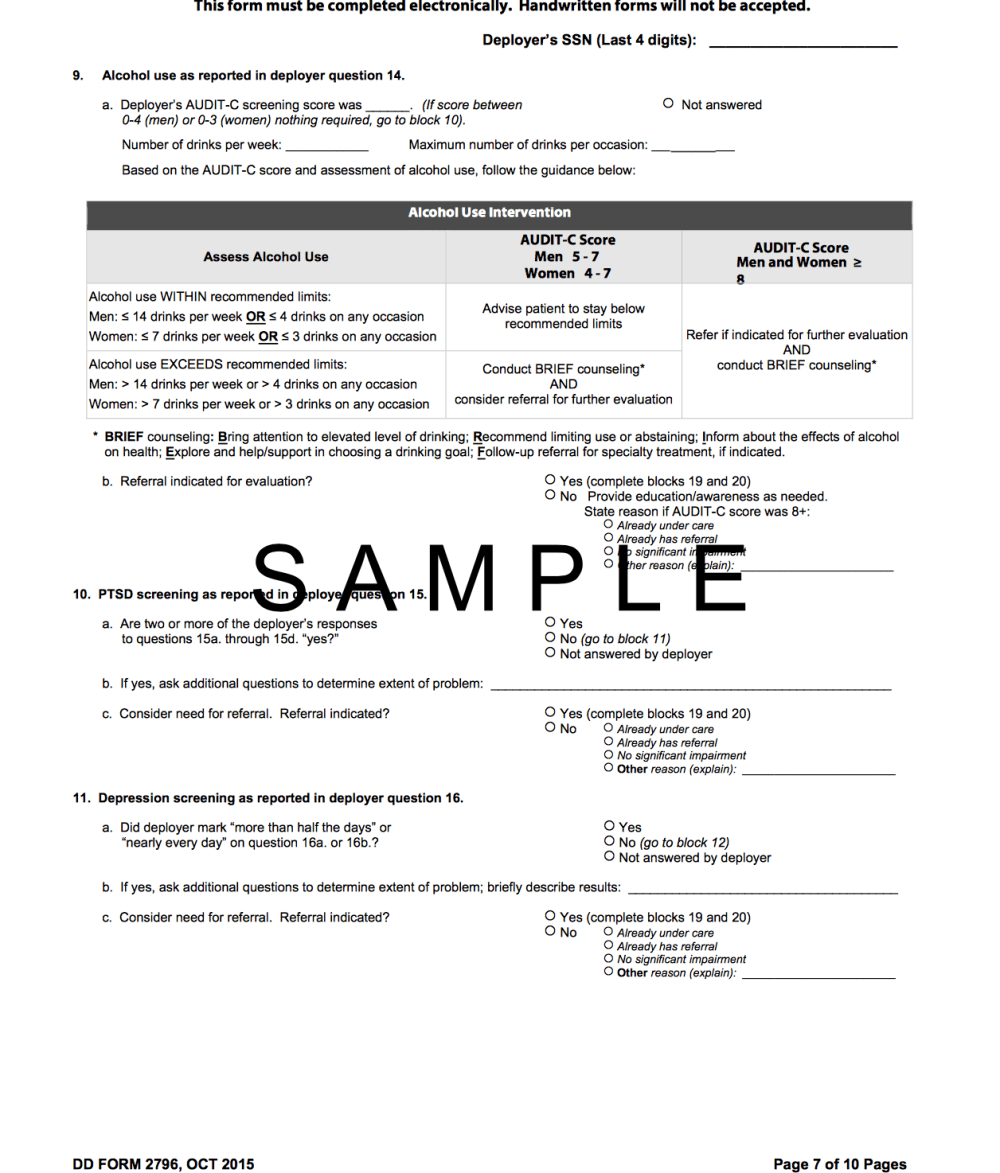

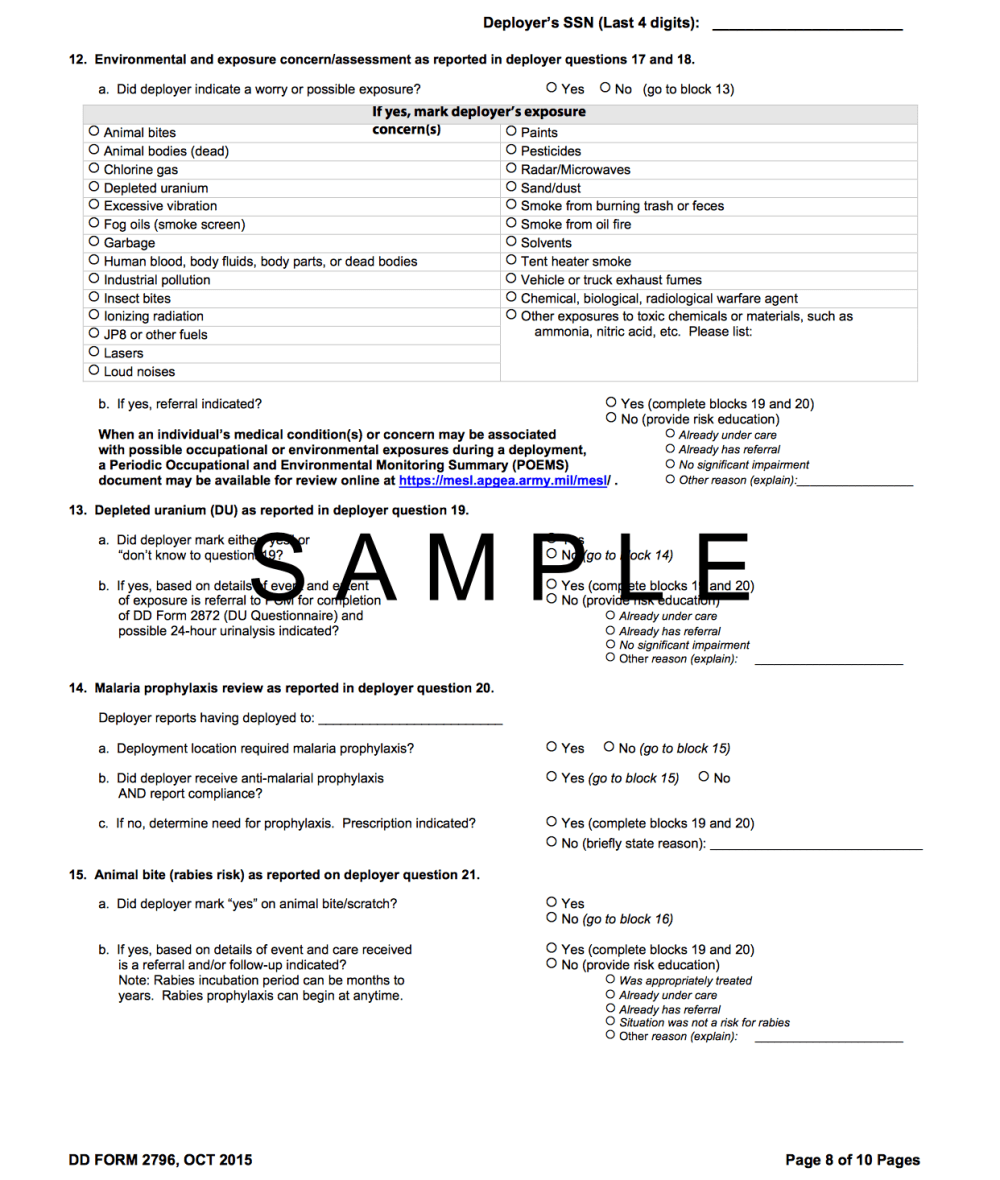

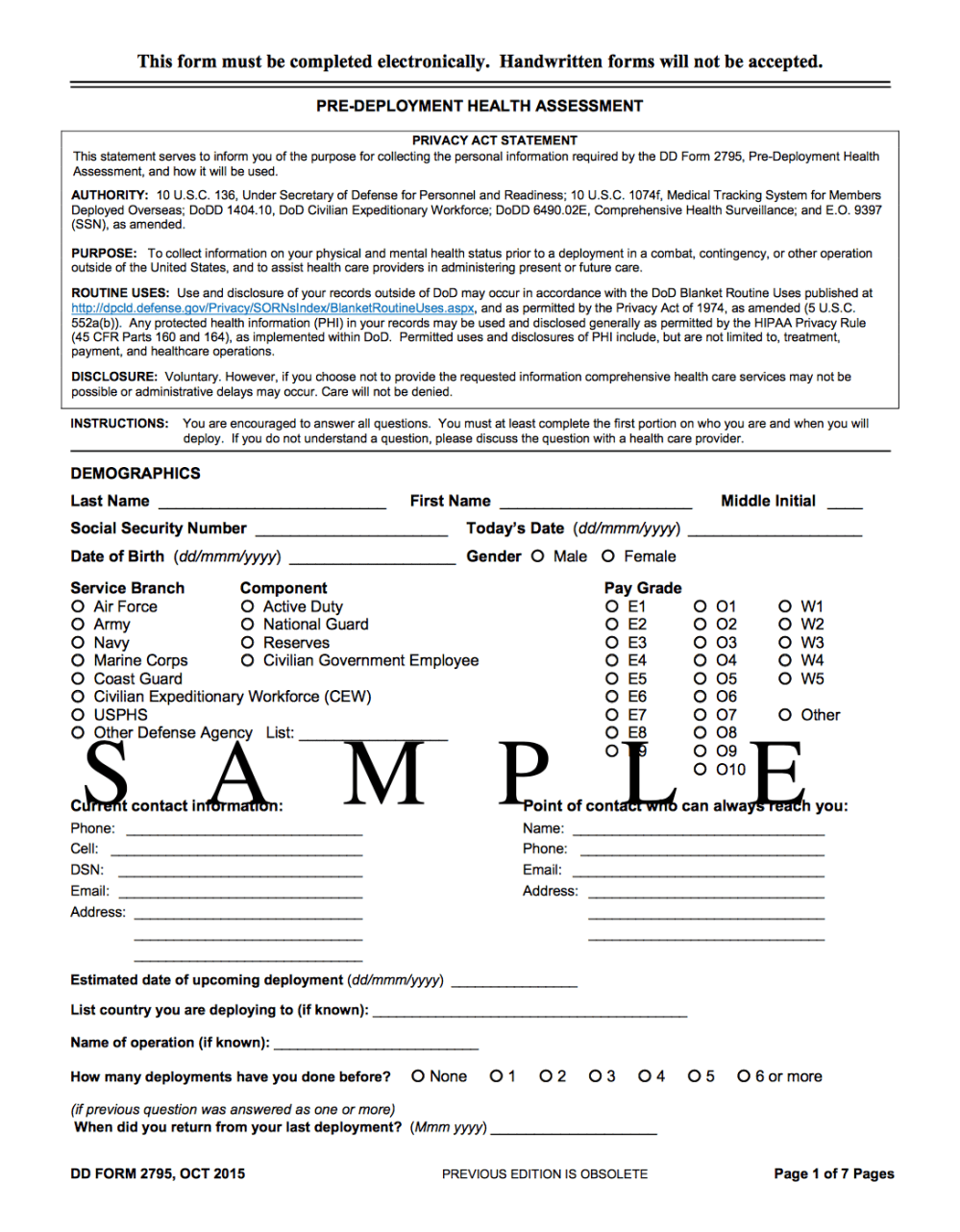

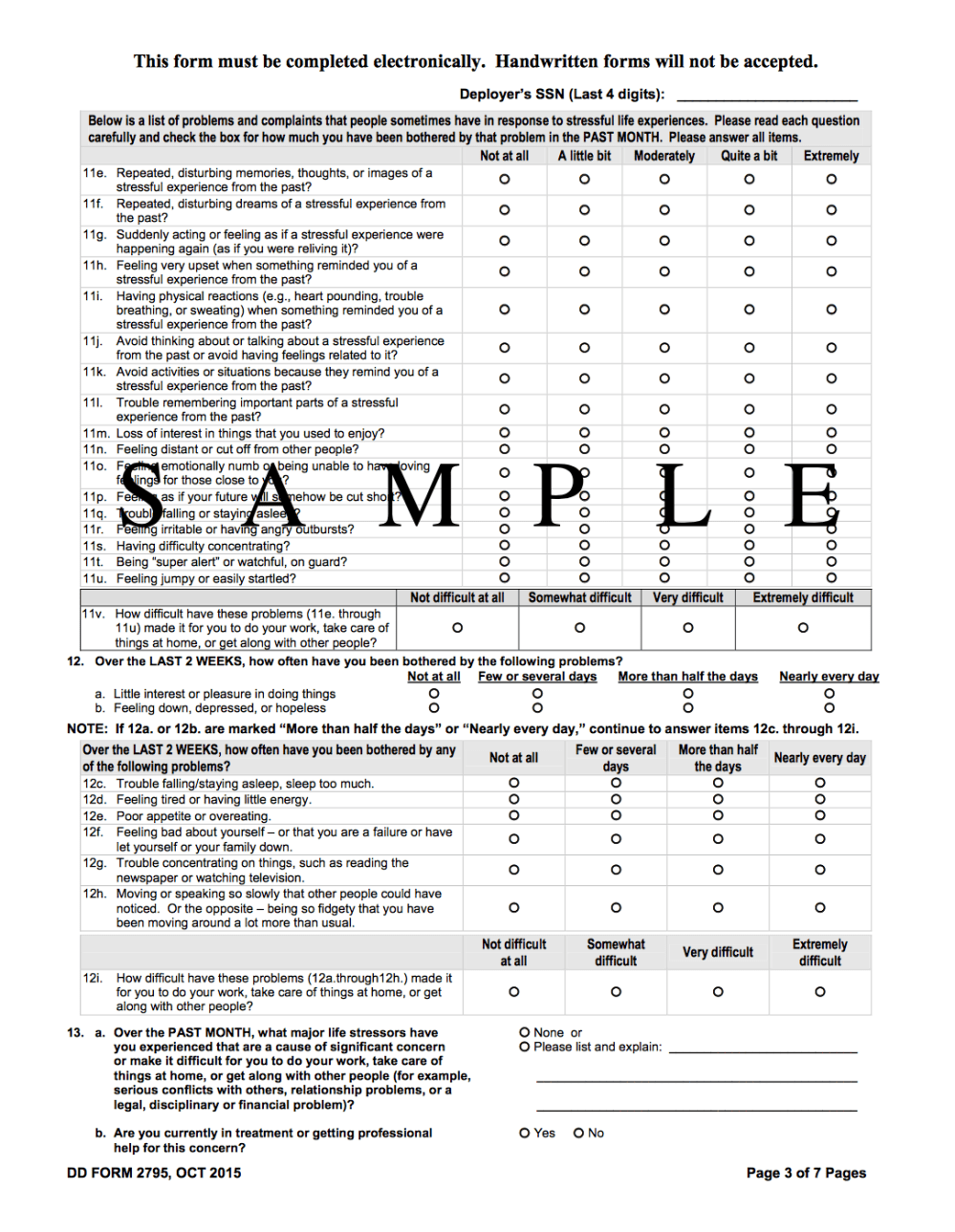

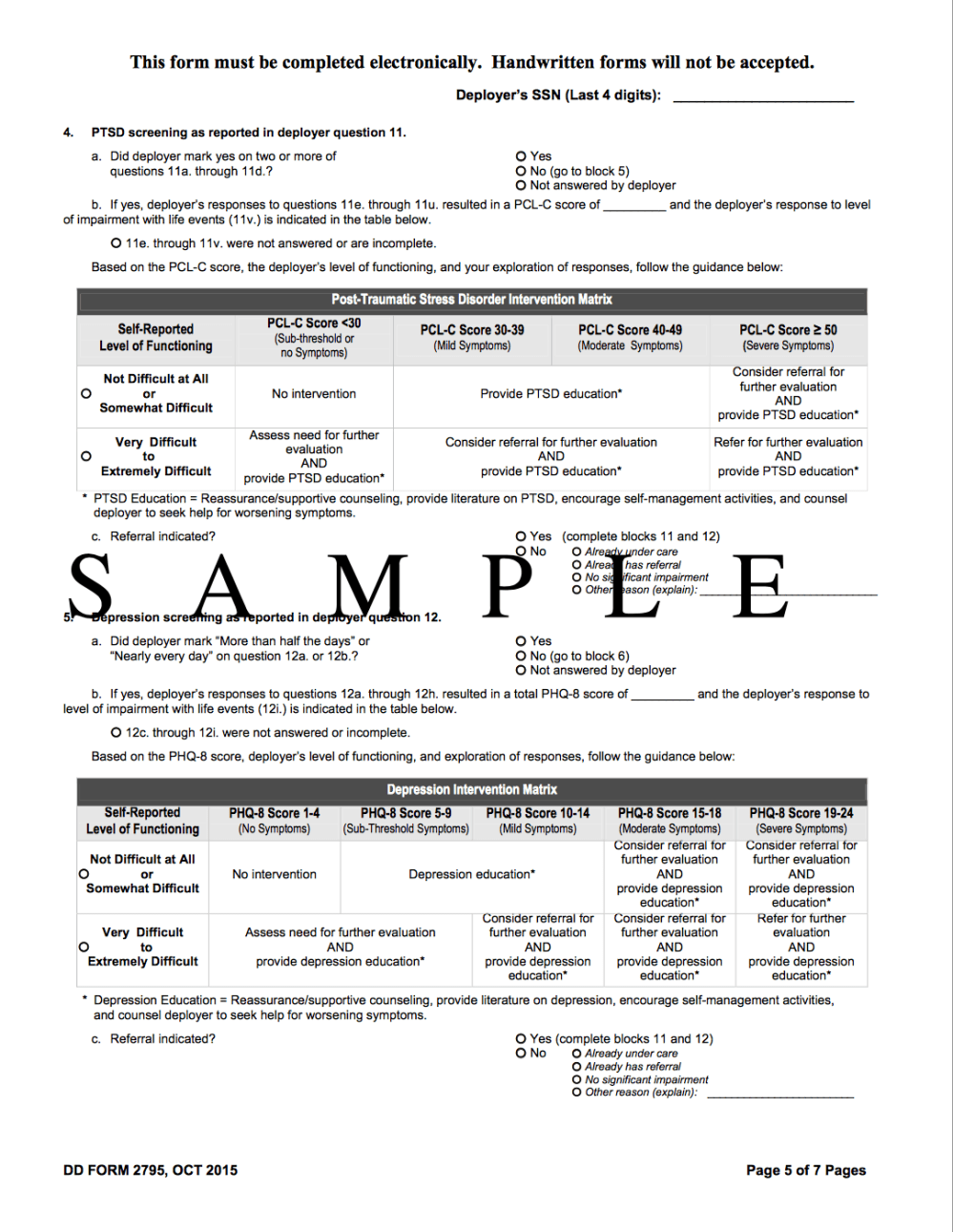

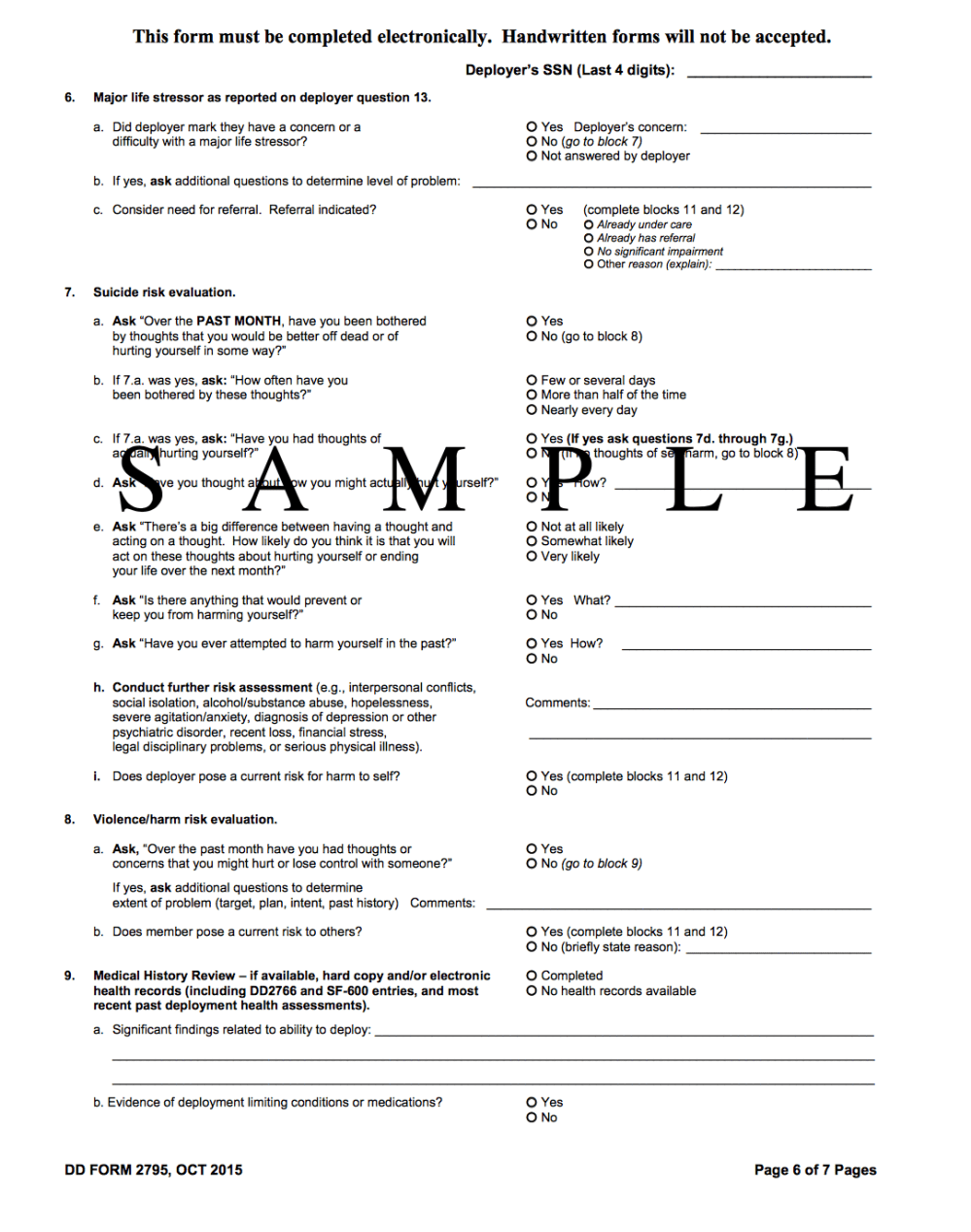

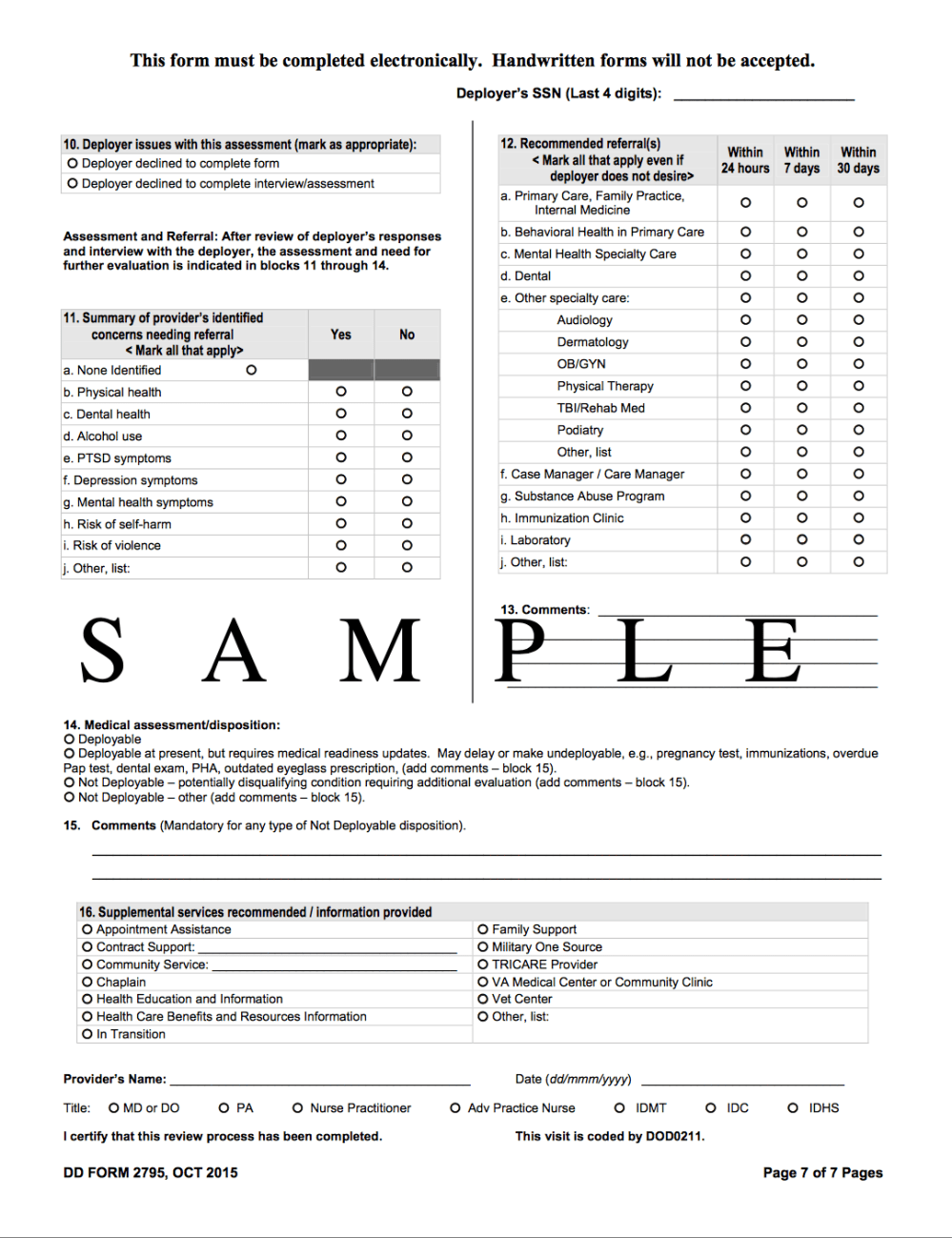

Below is the updated version of the Pre-Deployment Health Assessment Form:

The revamp of the Post-Deployment Health Assessment is also of great concern to me, and I think all veterans of this era should consider how the inadequacies of the earlier form shape what sort of service/deployment experience is considered valuable, dangerous, and potentially traumatic. The forum in which service members were offered to complete their forms is equally as important. I can remember completing the first form in a classroom with a number of guys, classroom style as though we were taking an examination for a grade. It was really a matter of “everyone’s got to do it”. You fill out your form by hand and turn it back in. You don’t want to get called out for your answers and you just want to make it back home.

I don’t recall completing the Post-Deployment Health Assessment at the end of my second deployment but most of the handwriting is distinctly mine; there are only a few segments where the medical personnel filled in information. Coming home was very rushed that time. I can remember meeting my husband and his mother and sister at the Sheridan, Wyoming airport but I cannot remember who picked me up in California. I remember having issues with my military gear being stuck on the conveyer belt and an older gentlemen picking up my pack like it was nothing, hoisting it up so I could tuck my arms into the shoulder pads and settle it on my back. (To everyone who was part of my transition home, I do not make this statement about not remembering your support lightly. Coming home was that much of a blur. I didn’t have a moment to catch my breath and will still say that process didn’t start until I left 3rd MAW in late May 2007 for terminal leave.)

My chest pains are the only thing I shared with the VA as a serious issue in 2007 and again, I am making the choice to share so much personal information because I don’t necessarily see our system getting better if there is a significant gap between what people expect their service to be like and the reality of the experience. I hope by cracking open an issue like poorly constructed pre-and post-deployment health assessments provides a lenses for organizations like the VA to understand where they must also take a step back and learn from veterans what deployments are like. I also hope current service members look at their needs before the needs of the organization they serve; at some point, we all leave the service and our personal health cannot take a back seat because we didn’t want to look like malingers/didn’t want to lose camaraderie/didn’t want to let down the team when a medical issue should have prevented us from deploying.

When I also decided to share with the VA this go around the fact I’ve dealt with tinnitus in the last few years and for a shorter duration, moments of hearing loss, I expected to have them listen. I thought it was fairly reasonable to be ‘heard’ since I have recorded mortar exposure in my records but never sought treatment because I didn’t notice anything wrong at the time.

Right now my hearing is not to the point where I’ve lost full functionality and I sincerely hope it doesn’t degrade further but the hearing loss does scare me. (The tinnitus, on the other, is mostly annoying and only occasionally causes pain.) These issues make me realize I cannot continue to take my hearing for granted and I should plan more for down the road if it degrades to the point where hearing aids might be needed. For now though, I am pretty good about asking people to repeat themselves when I need them to and I remind my daughter to come into the same room if she wants to talk to me. (She tries to yell from upstairs but I’m going to miss a lot of what she’s jabbering about so I make her come down and talk to me anyways.)

I am already past my bedtime (Seriously, it’s 10:45 pm!!!) but in closing, take a moment to look at the October 2015 form. It is much more inclusive. (Please excuse the fact I cannot obtain a good snapshot that shows on each page the form is not to be handwritten.)

I will continue my saga with the VA another day.