I don’t know that it will ever feel normal to witness war. Not that it should.

As a woman, I also have a different viewpoint. Men are often thought of as warriors and yet, I’ve been one. In fact, I still appreciate that my old boss in the Marine Corps called me ‘Warrior’ like the guys. I wasn’t singled out for being the only woman. In August of this year, it will be 20 years since I left for Iraq and that timeframe has been something I’ve marked rather subtly every year. It was a transformative experience. I miss how I used to smile more. Being so young and inexperienced in the world, I was in that ‘ignorance is bliss’ period we often find ourselves in. Afterwards, I was in a bit of a fight to not harm myself from how my life was unraveling, but I don’t regret how I became a better person overall. I went to Iraq with a lot of misconceptions about the country and its people.

Initially, I thought it was BS that the Iraqi people didn’t try harder to quash the insurgents infiltrating the country. What I didn’t understand in those early days on the ground is how much our presence as Americans in the country brought foreign fighters into an already distraught nation. When we took down Saddam Hussein, we left the country without a leader and trying to push our own democratic ideals were met with resistance. If the roles were reversed and a foreign military took out the American president, Americans would not be ready to lose their right to vote, their right to live without a military force stopping them on major roads and checking their persons and their vehicles, and our relatively unfettered access to food and water. The life we know as Americans would be replaced. A large portion of us don’t know what it means to go to bed hungry. Hospitals aren’t hard to find, but they aren’t drowning under a daily influx of severe trauma patients. Our social media accounts are often might currently cover personal successes, our purchases, and flaunt our travels. We aren’t employing them to voice concerns that every day might be our last (although any day can be someone’s last day).

War disrupts everyday life. Our nation hasn’t felt it first hand in quite some time, so we often cannot relate to others who are in the thick of it. For me, it’s been years since I walked in a war time environment. Other Americans might only read about it from the relative safety inside the classroom or at home as I did growing up. I read The Diary of A Young Girl by Anne Frank, like so many children around the world, when I was pretty young. I was either in late elementary school or early into my middle school studies. Having to hide so you are not murdered is not something anyone should experience. Children also cannot process trauma the same way adult cans and Anne Frank’s coverage of hiding the way her family did still impresses me. Children’s brains are still developing. Their whole beings have different needs than adults and any measure of starvation, lack of socialization, and loss of sense of security impacts them differently. Hers is not the only child’s portrayal of war that I encountered as a kid. I am not sure how long after the war in Sarajevo unfolded that I took up reading Zlata’s Diary: A Child’s Life in Wartime Sarajevo. The photos in this book are essential to the story that was published in 1993, in my opinion. The author, Zlata Filipovic, is only a few years older than me. Seeing war, in full color, from someone who could otherwise be my friend if we lived in the same area sat differently with me. I didn’t realize how normal of a childhood I was going through until I learned that kids just like me were living in wartime conditions. Later in high school, I read Night by Elie Wiesel. The way he doesn’t hide the horrors of war–in particular sharing a story of babies being used as target practice–is something we need to continue to discuss. When we soften the blow of war, we deny the harm that is going on.

My childhood was free of the stain of war. I was pretty young when my father served during the first Gulf war and I don’t really have a lot of memories from that time in my life, but a war that is thousands of miles away feels different for families than one right in their backyard. My mother and us kids were temporarily without the man who supported us; she lost her partner to share the burden of household and child rearing and us kids lost access to a parent who cared about our wellbeing and safety. His paycheck though still paid the bills and kept food on the table. I never lived in a nation that saw the value of its currency fall. I did not travel on foot to escape incoming munitions or hide from soldiers on the ground. My siblings and I were not robbed of our parents, like the plethora of orphans based on the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

The time I spent on the ground in Iraq taught me to empathize with the Iraqi people and the problems associated with our presence there. My introspections changed. I shared more with my family about life on base. We had a small Post Exchange (PX), a battalion aid station (BAS), a bank, a mail center, an AT&T phone center, a chow hall, and there were small housing enclaves for service members sprinkled through the base along with separate communities with Triple Canopy employees and a cordoned off housing arrangement for third country national (TCN) workers. Next year, it will be 20 years since I returned and it’s not completely abnormal to notice that our footprint in Iraq has some of the same problems of the European Americans taking over North America and relegating American Indians to reservations. Who wouldn’t want their land back? (Note: This is also a similar problem in places like Japan where service members’ drunken debauchery and physical and sexual assaults on locals, aircraft noise, and the excess imprint of American troops, equipment, and housing needs places a disproportionate burden on people not fairly compensated by our government and the military justice system doesn’t punish service members’ criminal activity in a way that serves victims’ needs and expectations.)

My experiences are why I have been stunned by how Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is devastating Gaza in retaliation of Hamas’ attack on Israel on Oct. 7th, 2023. His initial assault back on Hamas is definitely akin to the U.S. starting its War on Terrorism after 9/11. What I would have hoped is the decades we spent in Iraq and Afghanistan and the lessons from those wars (good and bad) were absorbed by him and he would not try to root out terrorists in a similar fashion. I think it’s ok that he had something he needed to do to address the assault on Israel. Given how much though Israeli intelligence failed to see the attack coming (again much like the attacks on 9/11), he should have carefully worked with the appropriate teams to selectively hunt down involved Hamas’ militants. He wasn’t going into a situation where there were clearly established military targets and training camps out in the middle of nowhere that would reduce the risk of civilian casualties in his response. Instead, he seems to relish that he’s devastating an entire population. And this is not a popular view at all, but others have already said it, how does he not see that his response in wiping out civilian Palestinian lives in Gaza is really starting to look like Israel has tragically forgotten what it is like for Jewish people to be hunted just for being Jewish by the Nazis?!

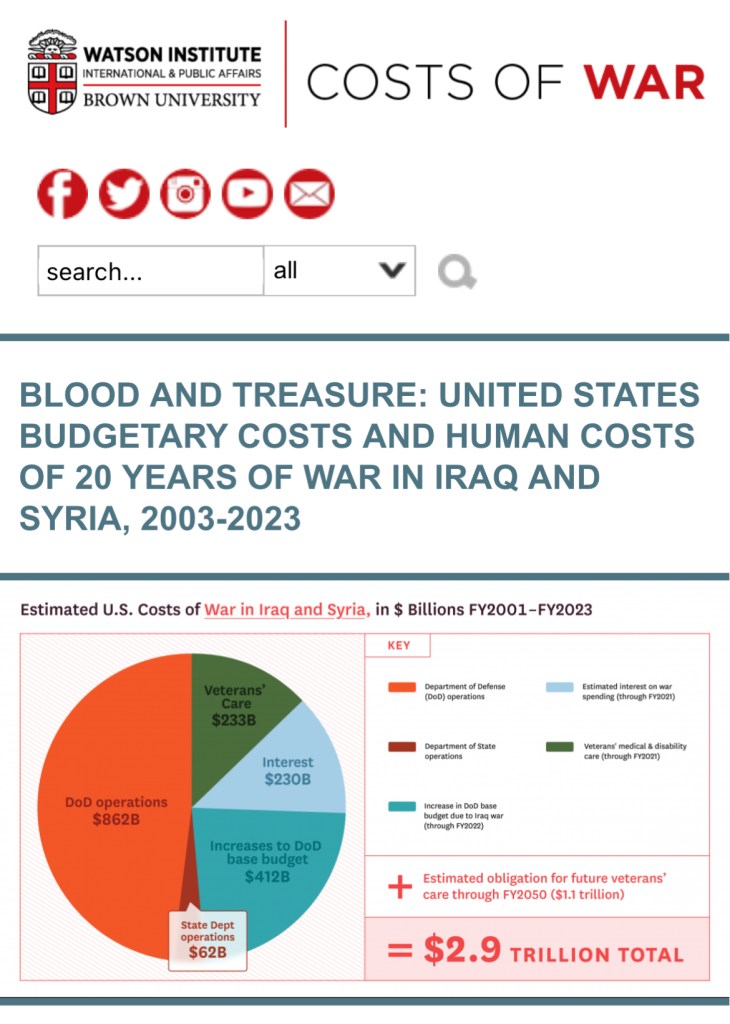

We made a lot of mistakes in our history here in the United States. I won’t lie and say we haven’t, but especially with the messy withdrawal in Afghanistan and continuing instability there and in Iraq, Israel had an easy reference on certain things not to do in response to terrorist events. No one is saying let the assault on Israel fall by the wayside, but his relenting attitude to punish Palestinians for an overall system many cannot change at this time has harmed not only Palestinians young and old but he is also endangering the lives of the Israeli hostages still held captive. He is risking their lives in his arrogant goal to rid the world of Hamas. He doesn’t seem to care that even if he’s successful in rooting out Hamas, the amount of people he’s angered has ruined a lot of global relations. He seems to not care that the very Israelis he indicated he wants back might die at the hands of his country’s service members. He really seems not to care that taking out some terrorist groups is very similar to pulling weeds and doing a poor job of it, ignoring the fact that other weeds are going to crop up soon. Again, because I don’t want to look like I am ignoring the United States’ war involvement in the Middle East, I encourage others to look at some of these numbers. I pulled this information off of Brown University’s Costs of War.

What originally got me started on this post today was a photo I saw recently. The photo you see below. The full story behind is is available here.

The female soldiers’ quest to document history, in selfie form, is not new. I just noticed how different it was from my service experiences. My unit and I would take photographs in areas that were well-established as ours, albeit temporarily. On Camp Blue Diamond (outside Ramadi, Iraq), the base that used to belong to one of Saddam’s sons, I photographed the outside of the blown up JDAM palace, our command center, my barracks, a view of the street and the street sign reading All American Way. When I photographed other Marines and myself, it was us in a very contained way. We were in our barracks, inside our work building, riding in a vehicle, etc. On the second tour, I was stationed at Camp Al Asad (in the vicinity of Al Asad, Iraq) and my photographs were mostly the same. My peers and I took some photographs on the base and around non-serviceable aircraft. There were a few of us screwing around with our decon system truck and we had essentially a large dishwashing foam playful fight outside our warehouse. On both tours, there are stoic photos of us and ones where we’re smiling. There are no shortages of weapons in the shots.

What’s missing though is a view of active destruction.

I don’t know that I could ever take a photo of myself smiling in front of a destroyed community. Even something like a memorial site is something I feel is off limits. I’d be just as offended for someone to smile in front of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. I’d be disgusted for someone to pose with an Outfit of the Day post in front of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. A carefully crafted selfie at the Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial would also make me cringe. It is not that I am opposed to photographing these sites and building an understanding of what occurred, it is simply that I don’t think we should be prancing around in such a manner on an area where mass casualties occurred. I am ok with being a photographer capturing the landscape and the absence of people. I appreciate showing the preservation of history (the maintenance of historic buildings, museum artifacts, etc.) and discussing what it means to be physical present at site versus just learning about it in a classroom.

As an example, the year my mother died, my dad took my siblings and I to Washington D.C. and we visited a number of museums and sites during our brief stay. I cannot etch it all into memory. Aside from our collective groan during the road trip that “Drops of Jupiter” was being over played, we bonded over seeing how our country recognized the sacrifice of our nation’s service members over the years. Standing before the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall made me feel incredibly small. The large expanse of names carved into stone starts slowly at one end and builds up until the wall intersects with another and slowly peters out until it is flush with the concrete sidewalk closely aligns with how war builds and comes to a conclusion. The way it is also cut into the earth leaves quite an impression: We are left with a strong message that humans are solely responsible for the construction of war and we have a duty to remember what happened to avoid it from occurring again. Walking next to the Korean War Memorial statues is something I struggle to express. You find yourself next to ‘persons’ in the middle of their military patrol and essentially witness their communication with each other. That ground level view is important as I think we’ve started to disassociate ourselves with the impact of war based on increasing use of military technology and think less of the human toll of war.

That’s why I wanted to share what I did today. I think the Israeli Prime Minister forgets he’s playing with innocent human lives in his ambition to eradicate Hamas and he seems to be ok with it. Again, I am ok with the fact he wants to get justice for the Israelis killed on October 7th, 2023, but he should be selective in his targets and bring to justice the Hamas assailants. Collectively punishing the Gazan populace is not the way to go and I still believe he should study past wars and their toll on local citizens so he can reduce the civilian death toll as much as possible.